The Basics

Ahh, NFTs… where do we even begin? What on earth is an NFT and why does that guy at the coffee shop with an ape on his sweater keep smugly talking about them? Does photography, a medium that we traditionally have come to understand as largely physical, have a place in this new format? This post is an attempt to distill these and other questions down to a digestible resource for my fellow photographers and others who find themselves curious about a virtual path for the future of photography.

There’s no better place to start than the basics — so, what is an NFT? I will keep this relatively simple. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are essentially a digital mechanism for the provable ownership of a digital asset. They do not represent a physical counterpart, but are instead a token that can cryptographically prove ownership (via the underlying technology of the blockchain) of what they represent. Some in the art world have come to think of this as a sort of Proof of Authenticity for digital goods.

Okay, I have a vague idea of what an NFT is and represents, so what rights am I giving up by selling a work of my art as a digital token? This is understandably one of the first questions by people deciding whether or not making NFTs of their work is viable for them. In most cases, unless stated otherwise, creators of NFTs retain the copyright of the work, and collectors have the right to display (privately or publicly) it for non-commercial use and have the right to sell, trade or transfer the work. There have been some instances where creators sell their work specifically with a CC0 Creative Commons license, which relinquishes the rights to their work and allows collectors to use it publicly — but this has been very rare in the photography space to date.

Got it. So with all of that aside, I’ve heard that NFTs and crypto currencies are terrible for the environment so why should I consider taking part in that? This is a complex consideration that will ultimately depend on your own thoughts and research, but I will give my two cents and move on. Yes, the current conditions of Ethereum, which is the primary blockchain for most NFTs, are very resource intensive and take a toll on the environment in their current state. There is no denying this. The good news is that the team behind Ethereum is working to migrate to the next evolution of the protocol called ETH2.0, which will be entirely proof of stake and will no longer use mining for block validation. This will drastically reduce the energy consumption of the blockchain as a whole. Alongside this, many projects and protocols are releasing and operating “L2” solutions which are technologies that use proof of stake to process and store data on an isolated blockchain that interacts minimally with the main, more decentralized Ethereum blockchain. Technical aspects aside, this is an issue that is taken very seriously and there are many resources out there discussing it at length. There are also currently a number of NFT platforms already operating on Proof of Stake blockchains, but the largest market share is by far still on L1.

Photography and NFTs

Okay, phew! Now that we have some technical stuff out of the way, let’s move on to photography and its current state in the NFT universe. It is no secret that 2021 was a wild year for NFTs. Throughout all of the noise of PFP (profile picture) projects, meme-centric NFTs and social experiments, a few things have felt like they’ve stood out. These include generative/algorithmic art led by platforms such as Art Blocks and fxhash (RIP hic et nunc), AI/GAN (artificial intelligence) art, and most recently photography.

Why photography? Maybe it’s the inherent humanity represented in the medium or the recognition of value we already have assigned to it societally, but photographers have begun to really find their footing in this space and the collectors have responded with great enthusiasm.

Whether it be fine art, documentary or long-form projects, the response by collectors to quality, well-intentioned work has really taken hold, bringing photographers from all over the globe initial success in this new space.

Choosing a Platform and Reaching Collectors

The next question many have when deciding they're ready to make their work available as NFTs is what platform to do it on and how they might attract buyers once they have minted their work. As of the writing of this post, there are a few standouts in terms of platforms where photographers are finding success.

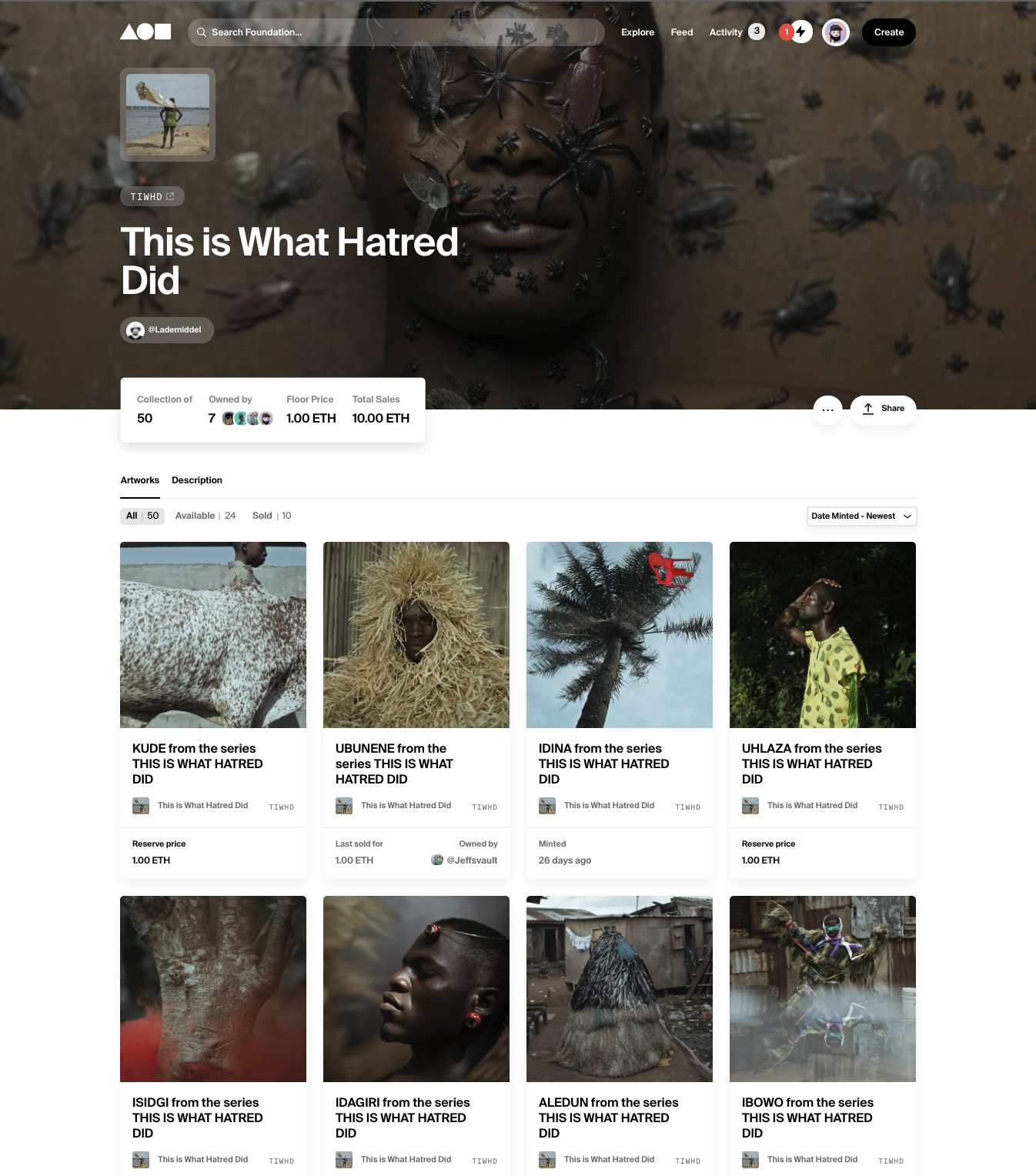

The first of these has to be Foundation (FND), which with their clean interface, decent discovery functionality and recent addition of collections has really jumped to the lead. With the implementation of collections, they made it possible for photographers to create their own smart contracts, which allows for great flexibility with controlling how the collection is shared on other marketplaces and how secondary royalties are established and collected. For example, a photographer with a collection on FND can customize the collection page for the work on a marketplace like OpenSea and set their secondary royalty percentage for sales that happen there, which is not possible when operating on other smart contracts outside of your control. Foundation also allows for the splitting of royalties if the work is a collaboration or a percentage is designated for charity. Currently, Foundation is available as invite-only with each new user getting three initial invites to disperse and then subsequent ones each time one of their invitees sells their first piece. The platform charges a 5% fee per transaction, recently reduced from 15%.

Cristina De Middel’s collection This is What Hatred Did on Foundation.

OpenSea (OS) is another simple option for minting your work. However, with limited search functions, no option for creating your own smart contracts and a less appealing layout, it hasn’t quite stood out like FND and others. One of the redeeming factors though is that the fee structure of OS transactions is quite low comparatively. OpenSea takes 2.5% of each transaction versus Foundation’s steep 15%. OpenSea is completely open for anyone to mint on.

Another option is Ephimera, which promised to be a platform for lens-based artists upon launching in 2020. Unfortunately, there has been little to no visible innovation to their interface over the past year resulting in a lack of popularity with collectors and making it a hard platform to recommend at the current time. Ephimera charges a fee of 10% per transaction and assigns a 10% royalty on the secondary market for sales done within the platform (secondary sales made on OS are a bit more complicated). Ephimera has an application process, which their website currently states is closed due to a large backlog.

An arguably more elite platform is SuperRare (SR), which recently has made a push to include more photography as opposed to its initial focus in other mediums. SuperRare is known for having high-end work and, as a result, tends to feature artists on the upper end of the pricing spectrum. SuperRare charges a 15% fee for primary transactions and have a 10% royalty structure for secondary sales. To be featured as an artist on SR, you must submit an application that includes a one-minute submission video (though there have been recent cases where this is not necessary).

Beyond these dedicated platforms and marketplaces is the option to deploy your own smart contract and make the work available on your own website or elsewhere. This can be done using tools such as Manifold or via a partnership with a smart contract writer. This allows one to have complete control over the terms of the work and eliminates just about all transaction fees, but is also an added level of complexity and potential lack of exposure.

In terms of how to attract buyers, it is important to understand the social aspects of the current NFT space more broadly. One thing I’ve learned over the past year is how powerful and validating personal connection is not only to artists, but to collectors as well.

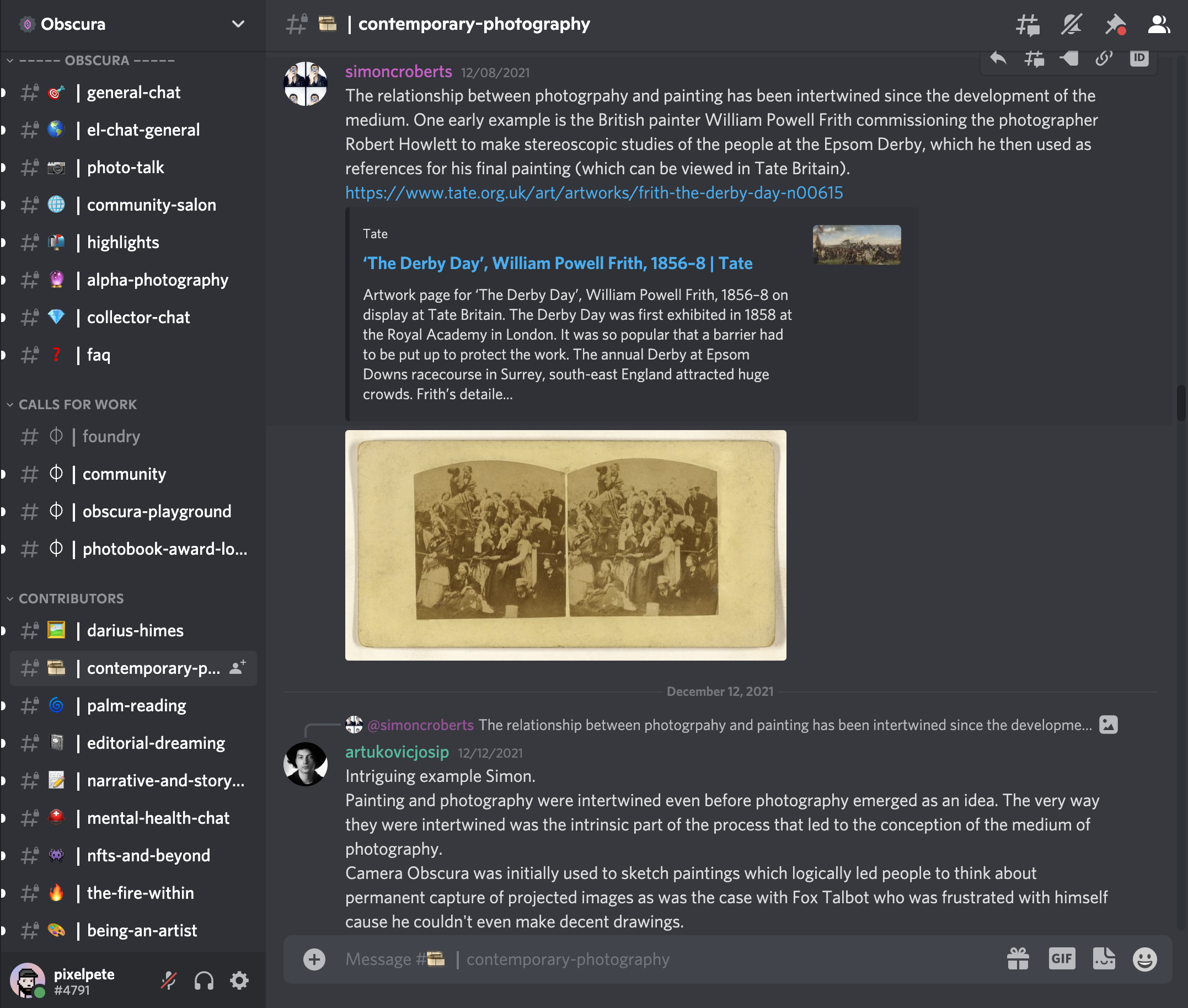

The NFT world is a largely social one that exists for the most part on Twitter and Discord. As someone who has spent most of their social media life in the Instagram ecosystem, I was slow to come around to Twitter, but have been really pleased with what I’ve found there once diving in. Now my feed is full of photography, positivity and sharing (and memes, of course), and is the first place I would encourage anyone entering the NFT space to start.

Screenshot from the Obscura discord.

For a deeper dive into the community aspect of things, Discord is the true ground zero. This can feel overwhelming to start, but there are a number of servers (linked below) that are specifically focused on photography and are full of incredible resources ready to engage. More than anything though, the best way to attract collectors of your work is to participate and engage with others within the community and to not be overly aggressive with selling.

Obscura - https://discord.gg/c65VMkfT

Assembly Art - https://discord.gg/JSjjERtr

Quantum Art - https://discord.gg/pEjrQXS7

Displaying Collections of Digital Art

Another mental hurdle some people have is thinking about how this digital work is meant to be displayed. Our default is to think in terms of the physical spaces we inhabit, but NFTs open up collecting in an entirely new way.

For one, we are not confined to collect only what we have the room to house. With NFTs, there has been an emergence in the variety of digital methods for displaying collected work. This can be in the form of virtual galleries that we can walk through in browser or using VR, scrollable galleries more akin to a traditional website, or a mixture of these and physical prints or books. One thing I’ve come to realize is that we are just in the beginning stages of how some of these emerging technologies will integrate with our current digital selves to create an entirely new and dynamic experience of sharing who we are and our artistic interests. Some examples of the ways users are expressing their collections are linked below.

A short walk thru of an OnCyber gallery.

https://www.studio137.com/photography/

https://oncyber.io/chikaiphoto/

Collectors are learning an appreciation and skill for curation in new ways too. I have seen many creators and collectors express how gratifying this aspect of the space can be. In the past, even if you know who might be collecting your work, it’s rare to see whose company it keeps and in what context. This new ability and thinking of how to collect and display works often is creating an immediate dialog between the work of several artists, often strengthening personal relationships with those creators, their collectors and outside viewers.

Lessons Learned and Getting Started

Lastly, I wanted to say a few words about some lessons I’ve learned from my own experiences and things I’ve observed from others.

For a long time, I wasn’t sure if or to what end photography fit into the greater NFT space. I began my journey through my involvement with generative art, which feels truly native to what NFTs offer and like a perfect fit. I was unsure whether photography would have the same validation in this purely digital space. It wasn’t until I was in a conversation in the Obsucra discord server when someone equated a RAW file as the digital equivalent to the film negative and how we can think of our processed digital images similar to a printed and processed negative, that I really began to see how these digital representations of our work could fit as part of the continued evolution of photography as a collectible medium. I am clearly not alone in this evolution in thinking, as is proven by the huge uprising in photographers and their collectors (old and new) coming into the space.

Upon entering the space, I initially felt that I had to change my work to make it more “digitally native” to be viable as an NFT. This resulted in first minting work that I had created years ago, mixing digital illustration with my imagery as well as some fun experiments in motion that in time I’m sure I will continue with. I’ve since learned that our still images hold just as much importance and relevance in this space as anything, and what’s important is strong work and storytelling. I’ve noticed this with several others who have struggled to find their initial footing, so I feel it is important to mention.

Still frame from Jeff Frost’s Sun Sine.

Finally, we can’t ignore the financial hurdles (and hopefully benefits) that are faced when first entering this unfamiliar space. As stated earlier, currently most NFTs are offered on the Ethereum network and alongside the rise of NFTs in 2020-21 came a rise in the price of crypto currencies, including Ethereum. To mint work onto a platform, you will have to pay gas in order to process the transaction and pay for the storage of the digital file your token represents. These costs can be substantial (think ~$75-150/high res image) and should be considered when thinking about how you price your work once it’s listed. A little research into gas fees and how to know when the best times to mint to avoid higher fees will go a long way.

No one can say with certainty where NFTs will go from here, but what feels certain to me is that they are not going away and that they have provided an abundance of opportunity to those willing to explore the possibilities.

I hope this post helps shed some light and encourages others to dig a little beneath the surface to see if there’s a place for you and your art. I’ll be waiting, anxious to share and collect your work in my virtual world.

Peter Molick (pixelpete) is an architectural and fine art photographer based in Texas. He is an advisor and curatorial board member to Art Blocks, advisor to Assembly, and has become an avid collector and proponent for NFTs.